![[CIRCULAR STARTUP TOKYO] Event Report | 4th Circular Business Design Lecture: “Circular Economy and Product Design”](https://harch.jp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/circularstartuptokyo-4th-lecture-report-202504-01-825x340.jpg)

[CIRCULAR STARTUP TOKYO] Event Report | 4th Circular Business Design Lecture: “Circular Economy and Product Design”

- On Jan 7, 2025

- Circular Business Design, Circular Economy, CIRCULAR STARTUP TOKYO, Product Design

As part of the second phase of “CIRCULAR STARTUP TOKYO”—a startup support program specializing in the circular economy, conducted in collaboration with the Tokyo Metropolitan Government—Harch Inc. held the 4th lecture of the Circular Business Design series, titled “Circular Economy and Product Design”.

*This article is a republished report from CIRCULAR STARTUP TOKYO titled “[Event report] 4th Circular Business Design Lecture: “Circular Economy and Product Design”.

Report on the 4th Circular Business Design Lecture: “Circular Economy and Product Design”

CIRCULAR STARTUP TOKYO is an incubation program dedicated to supporting startups in the circular economy sector. Over a five-month period, participants receive mentoring from entrepreneurs and experts active in the circular economy, attend lectures on circular business, and have networking opportunities with domestic and international circular economy promotion organizations, major corporations, financial institutions, investors, local governments, and specialists. The program aims to assist participants in building and growing new business models that contribute to the realization of a circular economy, ultimately aiming to secure funding and generate social impact.

On December 13, 2024, the fourth Business Design Lecture and the third Circular Economy Startup Practice session were held. The event featured guest lecturers including Katsuaki Sato, Representative Director of BRIDGE KUMAMOTO and CEO of Katsuaki Inc.; Misaki Tanaka, Social Designer, Representative of SOLIT, and CEO of morning after cutting my hair, Inc.; and Yoshiharu Hamada, Professor at the Product Design Laboratory of Tama Art University.

In the first half of the session, titled “Circular Economy Startup Practice (3),” Sato and Tanaka shared insights from their respective ventures, discussing key considerations and indispensable thought processes in social business aimed at solving societal issues.

In the latter half, Hamada delivered a lecture entitled “Circular Economy and Product Design,” addressing the role of product design in the circular economy, as well as the significance and practical methods of prototyping.

This article provides excerpts from these sessions.

*About the Circular Business Design Lectures

The Circular Business Design Lecture consists of five sessions. The first session provides a broad perspective on system design before progressively narrowing its focus to business design, service design, and product design in later sessions, delving deeper into the process of building circular businesses.

Identifying the Stage of the Issue and Applying the Right Solutions

The session “Circular Economy and Startup Practice (3)” led by Sato and Tanaka began with lectures based on their business experiences.

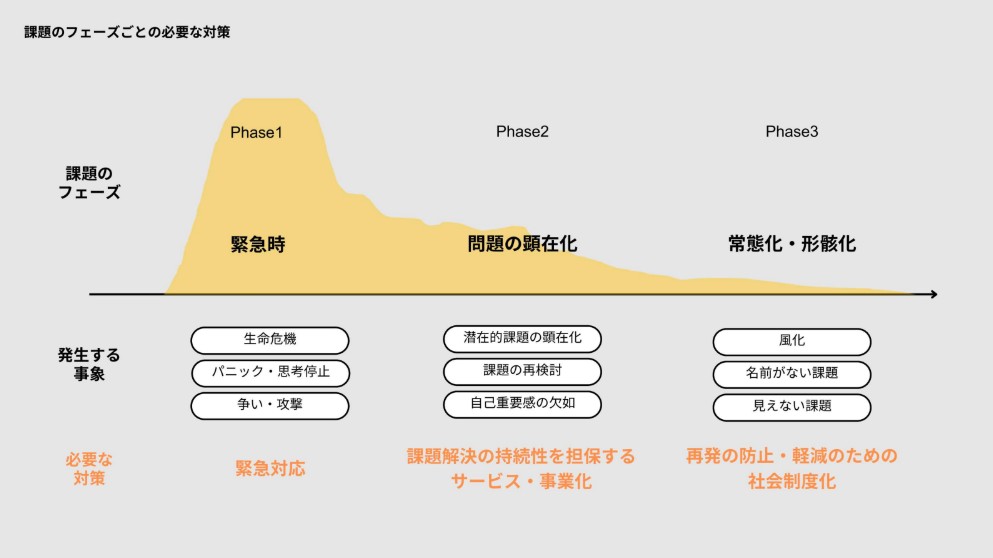

Tanaka emphasized the importance of identifying which stage a social issue is in and determining the appropriate solution accordingly. She categorized social issues into the following three phases:

Phase 1: Emergency

Phase 2: Issue Manifestation

Phase 3: Normalization/Formalization

Image via SOLIT

She highlighted the necessity of identifying which phase an issue belongs to and adopting corresponding approaches: emergency response for Phase 1, sustainable services or business development for Phase 2, and institutionalization for Phase 3.

Social Designer / CEO of SOLIT / CEO of morning after cutting my hair, Inc. Misaki Tanaka

Tanaka then introduced specific projects she has undertaken to address these issues. Considering her own strengths, energy, and age, she chose to approach problem-solving in a light-hearted, accessible way. This led to the establishment of the brand SOLIT!, which proposes fashion services as new forms of diversity representation and self-expression.

Tanaka stated, “When considering approaches to solutions, especially through business, it’s crucial to clearly define what the desired outcome of solving the issue looks like.”

Aiming for Problem-Solving through Organizational Design at SOLIT

Tanaka further discussed how SOLIT! strives to solve issues by designing not only products and services but also the entire organization’s systems and mechanisms sustainably.

Image via SOLIT

In SOLIT’s business, decisions are based on the hypothesis that “the root of issues like climate change and human rights violations lies in the continuous series of small, well-intentioned but ignorant decisions we make (fallacy of composition) and an excessive capitalist economic system.” Under this hypothesis, SOLIT promotes the design of organizational structures that consider human diversity and the global environment throughout the entire company management process.

Tanaka explained, “For example, our company’s articles of incorporation state that we are an organization established for the global environment and human diversity, and not primarily for profit pursuit. Therefore, we only contract with external stakeholders who engage in activities aligned with these articles.”

Social Designer / CEO of SOLIT / CEO of morning after cutting my hair, Inc. Misaki Tanaka

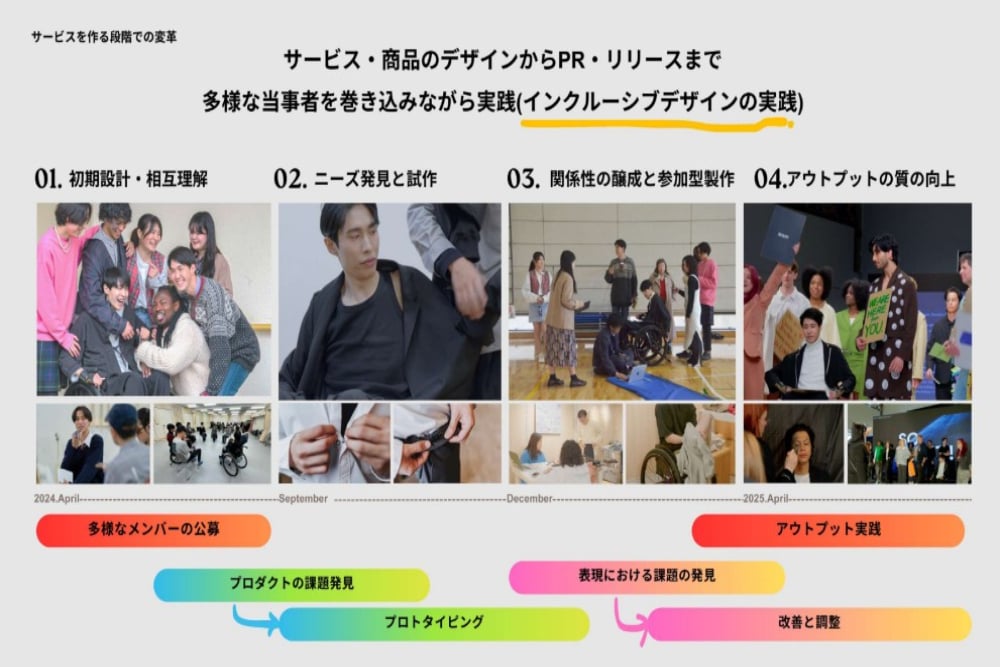

Additionally, SOLIT! has introduced a unique method called the “Radical Participatory, Inclusive Design Process” in its product design. This approach aims to address issues such as structural privilege within organizations and the perpetuation of existing problems in the design process. It stems from a critical perspective on traditional design systems and inclusive design.

Tanaka noted, “We believe that conventional design systems and the concept of inclusive design may inherently contain structural discrimination and colonialist aspects. The structure where we, who have economic power, abundant knowledge, and no worries about tomorrow, design for social minorities, people with disabilities, and those who previously had no choices, may already embody discrimination and structural issues. We aimed to change this design framework.”

Therefore, SOLIT! practices a unique design process involving various stakeholders in every stage, from service and product design to PR and release. Furthermore, they conduct external evaluations such as impact assessments and disclose information to stakeholders through sustainability and inclusive reports to assess whether their actions are truly contributing to solving social issues.

Image via SOLIT

Tanaka emphasized, “In pursuing essential design, we prioritize consistency and avoid superficial or partial approaches. We aim to continually improve by critically examining our efforts and collaborating with peers who can engage in equal discussions.”

Contributing to Social Issues Through Upcycled Products

The next speaker was Katsuaki Sato, Representative of BRIDGE KUMAMOTO and CEO of Katsuaki Inc. Based in Kumamoto, Sato usually works on creative direction and branding for manufacturers. In this lecture, he presented various case studies of upcycled product design that contribute to solving social issues.

Representative Director of BRIDGE KUMAMOTO / CEO of Katsuaki Inc. Katsuaki Sato

He first introduced the “Blue Sheet Bag,” a product that originated from the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake. During the disaster, approximately 190,000 households were affected, leading to a large-scale use of blue tarps—many of which later became waste. In response, a project was launched to collect the used tarps, clean them, and repurpose them into bags. These bags were sold to the public and through collaborations with companies and local governments, with around 2,400 units sold to date. Approximately 20% of the sales revenue is donated to disaster recovery efforts, and the usage of these donations is made publicly available on the project website.

Image via BRIDGE KUMAMOTO

Another product born from the aftermath of the Kumamoto earthquake was an omamori (Japanese charm) called Kōrai Furaku—meaning “never to fall again”—made using fragments of tiles that collapsed from Kumamoto Castle. The charms, produced by a local employment support facility for people with disabilities, have gained popularity among students preparing for entrance exams.

Image via BRIDGE KUMAMOTO

Outside of Kumamoto, similar upcycling initiatives have emerged. In the hot spring town of Beppu, for example, large quantities of bedsheets discarded by inns are repurposed into stuffed sharks named YUZAME. This project also collaborates with local employment support facilities, offering a model of upcycling that utilizes regional resources.

Image via BRIDGE KUMAMOTO

Despite the diversity of his initiatives, Sato emphasized that there are three consistent elements he always considers.

“What I focus on is: first, a clear concept and its articulation; second, a high level of design completion; and third, clarity about who benefits from the product. In addition to a compelling story, a project needs a sense of newsworthiness to gain broader recognition. However, when evaluating whether a project can succeed, I believe its value is not determined by market size, but by whether there is a strong sense of necessity—whether people want to do it or feel compelled to make it happen.”

Enhancing the Sustainability of Social Enterprises

A joint discussion followed, featuring both Tanaka and Sato. They addressed one of the core challenges of social business: balancing social impact with economic value.

They emphasized that social issues cannot be solved through rapid growth or expansion in a short time. Instead, long-term, sustainable business operations are essential. To that end, it is critical to design business styles and products that align with the nature of the issue being addressed.

(Left) Tanaka, (Right) Sato

The Role of Product Design in the Circular Economy Era

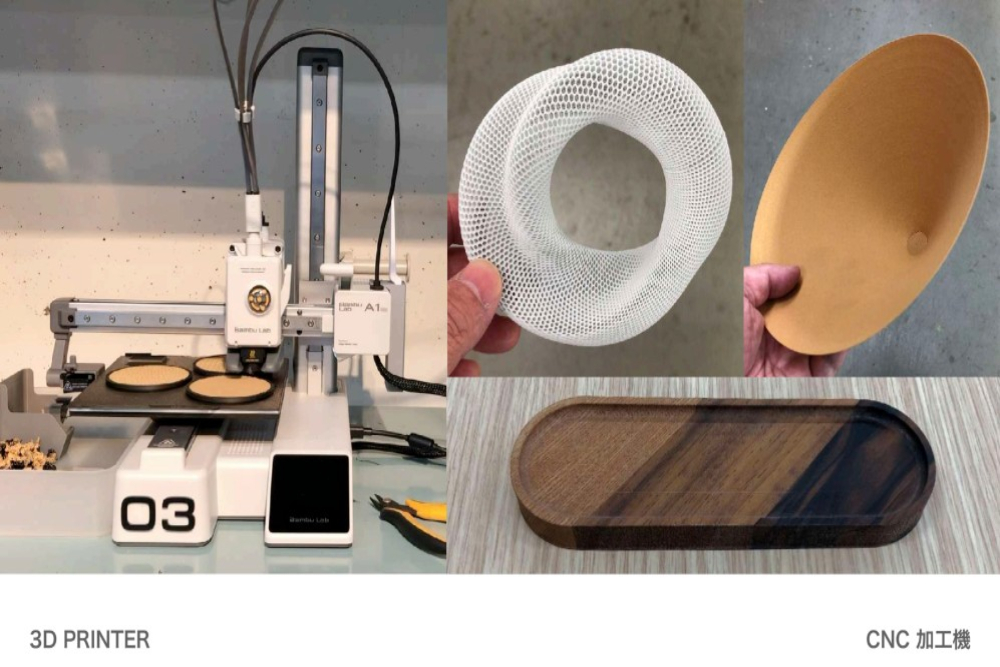

In the second half of the session, Professor Yoshiharu Hamada of the Product Design Laboratory at Tama Art University gave a lecture on the theme “Circular Economy and Product Design.”

Professor Yoshiharu Hamada, Product Design Laboratory, Tama Art University

Hamada began by discussing the evolving role of product design in today’s world.

“The original meaning of the word ‘design’ includes redefining existing things and creating new value. Today, designers are expected to work across physical products, interfaces, and services to craft seamless customer experiences.”

As such, his approach to product design goes beyond shaping physical forms—it considers the overall user experience and the systems behind it.

One of his initiatives, titled “Suteru Design (Designing Waste)” (in Japanese), seeks to transform discarded materials into products that possess “beauty” or “joy,” making people want to pick them up. This approach aims to raise awareness about circular and sustainable societies through everyday interactions with designed objects. He regularly prototypes new ideas with this goal in mind.

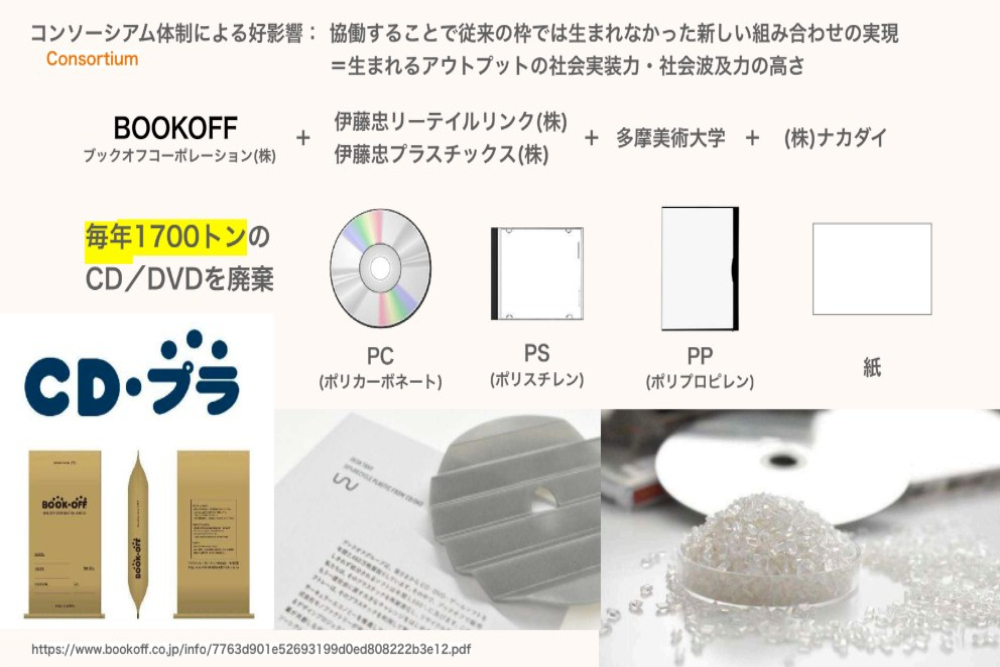

A specific example shared during the lecture was the CDpla project, which repurposes CD, DVD, and game software cases collected by BOOKOFF into recycled plastic used for creating new products.

Image via Hamada

Image via Hamada

Capturing True User Perspectives Through Prototyping

The next segment featured Hamada speaking on the topic of prototyping. While the broader definition of prototyping is “visualization,” its application varies slightly between design and business contexts.

In the design process, the goal of prototyping is to visualize ideas and give them form in order to test and verify their potential. On the other hand, in the context of business and design thinking, prototyping is used to uncover user insights. Hamada explained the latter using the “Five Steps of Design Thinking” developed by Stanford University’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design. He emphasized the premise underlying the framework:

“The problem you are trying to solve is almost never your own.”

“In most cases, the challenges we aim to solve through design or business are ones faced by the broader majority,” said Hamada. “However, since humans live in a world perceived through their own lenses, it’s incredibly difficult to see things from another’s point of view. Design-thinking-based prototyping is not about relying solely on your own experience—it’s a process to truly understand the user’s perspective and connect that to meaningful problem-solving.”

Hamada also stressed the importance of questioning the concept of “objectivity” before beginning prototyping.

Professor Yoshiharu Hamada, Product Design Laboratory, Tama Art University

“People often assume that multiple opinions are more objective than a single opinion. But in reality, that’s just a collection of subjective views. Objectivity lies in identifying commonalities—the overlapping parts across various viewpoints. However, this method makes it difficult to uncover new discoveries or latent needs. That’s why in prototyping, we employ the approach of ’embodying a specific individual.’ By standing in someone else’s shoes and making a genuine effort to understand their viewpoint, we gain deeper insights.”

He further introduced the concept of “step back” as a way to reconsider user challenges from a more fundamental perspective. For example, instead of asking “What is a bus?” when designing one, you might ask “What is mobility?” This approach broadens the distance between abstraction and specificity, enabling new discoveries.

In the prototyping process, narrative communication—creating stories with stakeholders while shaping the design—also plays a key role. In a project conducted with 105 elementary school students in Sagamihara City, Kanagawa Prefecture, discarded acrylic partitions were turned into collaborative art pieces. Before starting, Hamada conveyed to the children:

“We want your help to inform people about the problem of waste and the state of our oceans.”

Together, they created a shared opportunity to reflect on the ocean. The project not only taught children about marine plastic pollution, reuse, recycling, and upcycling, but also nurtured creative thinking and problem-solving skills.

To conclude, Hamada spoke on how design can be used to envision the future.

“There are many ways to envision the future, but I believe in the power of combining technology-driven and design-driven approaches. By adding a design perspective to technology-based ideas, we can go beyond simply solving problems—we can create futures that are more valuable, exciting, and full of joy. Using a backcasting approach to imagine the future we want, then breaking it down into achievable steps, is also key to making it a reality.”

Conclusion

In the first session, Tanaka and Sato introduced initiatives that harness organizational design and creativity to tackle social issues, with a focus on the Kumamoto and Kyushu regions.

In the second session, Hamada shared practical methods and frameworks from a product and design perspective, showing how prototyping can support the realization of desired futures. The lecture served as a meaningful opportunity to reflect on how to take a holistic view of one’s business from both design and business perspectives and translate that into concrete action.

The next session will include an academic intensive led by investment professionals, along with practical exercises in circular economy startup development. Participants will continue deepening their knowledge and refining their approaches as they prepare for business expansion and Demo Day. We look forward to seeing how each participant advances their ideas!

[Related Page] “[Event report] 4th Circular Business Design Lecture: “Circular Economy and Product Design”

[Related Site] CIRCULAR STARTUP TOKYO

![[Circular Yokohama] Event Report | YOKOHAMA CIRCULAR FASHION GATHERING: Envisioning the future of textile circulation across industries](https://harch.jp/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/YOKOHAMA-CIRCULAR-FASHION-GATHERING-300x200.jpg)